Rabbit Holes 🕳️ #110

From a schizophrenic internet to digital dependence, knowingness, cognitive decline, capitalism → post-growth, a post-normal science, ikigai revisited, and deconstructing the productivity machine

Hello and welcome to the 49 new subscribers who have joined us since last week, and welcome to another issue of Rabbit Holes!

THIS WEEK ↓

🖼️ Framings: Schizophrenic-Internet // Digital Dependence // Knowingness

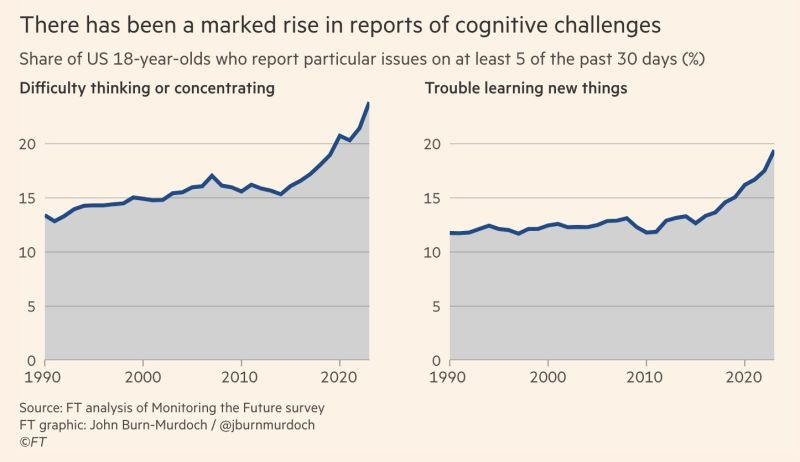

📊 Numbers: Cognitive Decline

🌀 Re-Framings: Capitalism → Post-Growth // Normal Science → Post-Normal Science // Ikigai → Meaning/Purpose Cycle

🧬 Frameworks: Creative Systems: Deconstructing The Productivity Machine

🎨 Works: Starline // The Future of Animal Wellbeing // The Resilience of Syrian Refugees

⏳ Reading Time: 8 minutes🖼️ Framings

Naming Framing it! Giving something we all feel more prominence in a way that promotes a deeper reflection.

🎭 Schizophrenic-Internet

My friend Stéphan shared this article with me, and I love the framing. The TL:DR is that we’re shifting from an ADHD internet that causes anxiety, overwhelm, and depression to a schizophrenic internet that causes paranoia. The piece and the framing tie a few things together that I’ve shared in this newsletter before, particularly one theme that I identified as a major shift for 2025: hyperreality.

There was a time— until let’s say, six months ago —when the dominant internet self-diagnosis was anxiety, depression, or ADHD.

Okay, yeah everyone was overstimulated exhausted, and constantly self-analysing through the lens of a WebMD symptom list. But lately, the discourse has shifted. The new digital state of being? Schizoposting. Mania narratives. Hyper-symbolism. Basically, the internet is having a psychotic break, and we’re all in the group chat.

We used to talk about the internet as an attention-destroying machine. Everything was about dopamine cycles, constant tab-switching, the inability to read a full article without drifting away. But the newer, more acute internet disorder isn’t just about fractured attention—it’s about fractured reality. […]

If ADHD internet was about jumping from one thing to another, schizo-internet is about the feeling that everything is connected.

The algorithm is designed to show you fractured, contradictory realities, all at once. One scroll and you’re seeing world news, conspiracy theories, a frog in a cowboy hat, someone’s breakup trauma dump, and a graph about how time isn’t real.

This hyperstimulation isn’t just about speed—it’s about paranoia. […]

Schizoposting thrives on this—mundane things become loaded with significance. Why do certain colours keep appearing in pop culture? Is this meme actually part of a secret message? Why does this TikTok feel like a prophecy? […]

The way platforms serve us information—fractured, unpredictable, contextless—creates a feeling of constant destabilisation. What’s real? What’s satire? What’s an ad? Who’s in on the joke, and who’s the joke about? This really adds some urgency to “touch grass,” huh?”

» The schizo-fication of the online world by Sophie Randell

👩🏾💻 Digital Dependence

We’ve created a world of constant acceleration that’s now increasingly hitting our own processing limits. The demand for more than what our brains and bodies can accomplish requires us to outsource more and more of our mental (and physical—it’s connected anyway) capabilities to technology. But be careful what you outsource!

“To keep up with the requirements of a knowledge sector job in 2025, you need more than your own mind. The standard for productivity has shifted dramatically in recent years. Under-resourced newsrooms, for example, require journalists to not only report and write, but also fact-check, monitor trends, and maintain a personal brand across multiple platforms. Software engineers face ever-tightening sprint deadlines while creating the very tools upending their jobs. Across fields, the processing limits of the human brain can’t compete with expectations of constant availability, instant information recall, and perpetual content creation.

Insisting on avoiding the tools in front of you can mean failing to meet increasingly high expectations. “If I’m going to see my doctor,” said Fisher, “I don’t want them to only give me information they’ve memorized. I want them to have as many resources at their disposal as possible to find the correct answer.”

In high-stakes situations, prioritizing accuracy over cognitive self-reliance seems obvious. The challenge becomes knowing where to draw the line.

Some tasks, like memorizing phone numbers and drafting insurance appeal letters, we’ve happily surrendered without much consideration. The patience and focus required to solve hard problems, however, seems worth holding onto. As a kid, I could sit and read a book for hours without even thinking about getting up. Now, I can barely read a single 800-word news article without feeling a physical compulsion to check Instagram.

It’s increasingly difficult to convince myself that solving a hard problem is actually worth solving when easier alternatives are just a click away. Why bother taking the time to write a LinkedIn post promoting my work, when AI can do it faster (and likely better)? Everyone else is doing it.”

» The case for using your brain — even if AI can think for you by Celia Ford

☝️ Knowingness

While growing social polarization is a key threat to democracy, knowingness might be an even bigger problem and a better, more suitable framing. This again ties in with many things I’ve shared here before, particularly with The Death of ‘I Don’t Know’ piece I shared a few weeks ago, which links this also to AI.

Knowingness is a term coined by […] the philosopher Jonathan Lear. It’s defined by a relationship to knowledge in which we always believe that we already know the answer—even before the question is asked. It’s a lack of intellectual curiosity, in which the purpose of knowledge is to reaffirm prior beliefs rather than to be a journey of discovery and awe. As Malesic puts it:

‘In 21st-century culture, knowingness is rampant. You see it in the conspiracy theorist who dismisses contrary evidence as a ‘false flag’ and in the podcaster for whom ‘late capitalism’ explains all social woes. It’s the ideologue who knows the media has a liberal bias – or, alternatively, a corporate one. It’s the above-it-all political centrist, confident that the truth is necessarily found between the extremes of ‘both sides’. It’s the former US president Donald Trump, who claimed, over and over, that ‘everybody knows’ things that were, in fact, unknown, unproven or untrue.’ […]

Understanding knowingness is crucial, because the antidote to it is different from the antidote to misinformation. If someone is only misinformed, you just need to provide them with correct facts and they can become rightly informed. But misinformation persists precisely because knowingness shields a person from learning.

[Malesic] ‘Knowingness is why present-day culture wars are so boring. No one is trying to find out anything. There is no common agreement about the facts, and yet everyone acts as if all matters of fact are already settled.’ […]

It feels good to be right, to prove others wrong, to win the combative joust that defines most of our national politics these days. But it feels even better to learn. The point isn’t to acquire knowledge to eliminate ignorance. That’s impossible. Instead, it’s to treat knowledge as the joy of discovery.

» "Knowingness" and the Politics of Ignorance by Brian Klaas

📈 Numbers

A thought-provoking chart that perfectly captures a pivotal shift:

There is more thought-provoking content to explore below for paid subscribers:

🌀 Re-Framings: Capitalism → Post-Growth // Normal Science → Post-Normal Science // Ikigai → Meaning/Purpose Cycle

🧬 Frameworks: Creative Systems: Deconstructing The Productivity Machine

🎨 Works: Starline // The Future of Animal Wellbeing // The Resilience of Syrian Refugees