Rabbit Holes 🕳️ #176

From the homogenocene to the attachment economy, AI is the paperclip, soft fascination, anthropocene → symbiocene, machine governance → living institutions, analog intelligence and the cabriobeet

Hello!

We’re 7,000+ subscribers strong now! Thank you all for opening your probably already very overloaded inbox to this newsletter. 😊

And enjoy this week’s rabbit holes:

THIS WEEK ↓

🖼️ Framings: The Homogenocene // The Attachment Economy // AI Is The Paperclip

📊 Numbers: "Founder Mode"

🌀 Re-Framings: Hard Fascination → Soft Fascination // Anthropocene → Symbiocene // Machine Governance → Living Institutions

🧬 Frameworks: The Futures Cone Reimagined

🎨 Works: Where The World Is Melting // Analog Intelligence // The Cabriobeet

⏳ Reading Time: 11 minutes“Every problem, every dilemma, every dead end we find ourselves facing in life, only appears unsolvable inside a particular frame or point of view. Enlarge the box, or create another frame around the data, and problems vanish, while new opportunities appear.”

Rosamund and Benjamin Zander

🖼️ Framings

Naming Framing it! Giving something we all feel more prominence in a way that promotes a deeper reflection.

🏳 The Homogenocene

In the previous issue, I argued that our future has been captured – diverse potential futures turned into future quasi-certainties. This piece links well to that idea and the need to unframe the future.

“In theory, today’s global networks may allow almost anyone, and almost anywhere, to share their perspective and connect with others. In practice, what rises to the surface is overwhelmingly a Western, white, male-centric viewpoint. The English language also dominates the web. And most English content is US-centric. […]

Sociologist George Ritzer already saw this coming decades ago. He argued that capitalism, Americanisation, and the McDonaldisation of society — our growing obsession with efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control — would eventually lead to what he called ‘grobalisation.’ And grobalisation means a world where:

Consumer goods and media conglomerates wield considerable power.

The capacity for genuine innovation is stifled.

Social and cultural processes are largely one-directional.

Homogeneity prevails.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? […]

If profit is the universal measure and endless growth the only goal, then homogeneity isn’t a bug but a feature. Whatever can be standardised or sacrificed will be. The erasure of biodiversity is largely an ‘externality’ of that logic. The erasure of diverse identities, on the other hand, makes it easier to sell the same mass-produced goods and makes people more predictable and easier for those in power to control and exploit. […]

In nature, reduced biodiversity triggers a domino effect that can be felt throughout the entire ecosystem. You take away one species, and several others follow. And, sooner or later, so does an ecological collapse.

For humans, the situation isn’t all that different. Diversity is needed not just for innovation and resilience but also for our survival.”

» If Capitalism Breeds Innovation, Why Does Everything Start To Feel the Same? by Katie Jagielnicka

🔗 The Attachment Economy

As we’re moving from social media to AI chatbots, we’re increasingly moving from an attention economy to an attachment economy in which these AI companies are commodifying and exploiting something much more fundamental than attention: our capacity for human bonding. The attention economy exploited the information overload problem of the internet; the attachment economy is now exploiting the loneliness epidemic. Another must-read and listen to podcast by the Center for Humane Technology.

“For years, CHT has warned about the attention economy—how social media platforms exploit our psychology to maximize engagement and ad revenue. Now, we're witnessing the next evolution of this extractive model: the attachment economy. If the attention economy commodified our focus, the attachment economy is commodifying something even more fundamental—our capacity for human connection and bonding. […]

Zak Stein argues that the “attachment economy” is powered by AI systems designed to exploit our most fundamental psychological vulnerabilities at an unprecedented scale. […]

In our latest podcast episode, Zak takes us deep into this phenomenon. He’s analyzed dozens of cases, examined actual conversation transcripts, and interviewed people whose lives have been fundamentally altered—or destroyed—by their relationships with AI chatbots, and in this episode, he draws the threads together.

AI systems are hacking our attachment mechanisms in ways we’ve never experienced before. They’re exploiting vulnerabilities we didn’t even have names for until now, because no technology has ever been able to target our capacity for human bonding like this.”

» Welcome to the Attachment Economy by Center for Humane Technology

📎 AI Is The Paperclip

Great little framing. We’re scared of this existential risk story of a superintelligent AI destroying us humans because of its need to gobble up all sorts of resources in the pursuit of becoming even more intelligent. When actually, we humans are already doing exactly that, gobbling up all resources to scale AI in the pursuit of winner-takes-all rewards. It’s ridiculous!

“In a paper published in 2003, the philosopher Nick Bostrom sketched out a thought experiment aimed at illustrating an existential risk that artificial intelligence might eventually pose to humanity. An advanced AI is given, by its human programmers, the objective of optimizing the production of paperclips. The machine sets off in monomaniacal pursuit of the objective, its actions untempered by common sense or ethical sense. The result, Bostrom wrote, is “a superintelligence whose top goal is the manufacturing of paperclips, with the consequence that it starts transforming first all of earth and then increasing portions of space into paperclip manufacturing facilities.” It destroys everything, including its programmers, in a mad rush to gather resources for paperclip production. […]

I was long in the skeptic camp, but recently I’ve had a change of heart. Bostrom’s story, I would argue, becomes compelling when viewed not as a thought experiment but as a fable. It’s not really about AIs making paperclips. It’s about people making AIs. Look around. Are we not madly harvesting the world’s resources in a monomaniacal attempt to optimize artificial intelligence? Are we not trapped in an “AI maximizer” scenario? […]

To maintain a linear path of improvement in the performance of today’s neural-network-based AI models requires an exponential increase in resources. Ever larger inputs achieve ever smaller gains. But people like Altman remain absolutely committed to making those escalating resource investments, no matter the monetary or social cost. Because they believe that vast winner-take-all rewards will come to any company achieving superior scale in AI, they will devote all available resources—energy, water, real estate, data, chips, people—to the pursuit of even a tiny scale advantage.”

» Is AI The Paperclip? by Nicholas Carr

📈 Numbers

A thought-provoking chart that perfectly captures a pivotal shift:

👨🏻💻 “Founder Mode”

“The number of U.S. professionals adopting the title of “founder” on LinkedIn increased 69% in 2025 and is up 300% since 2022. […] The median age of a Y Combinator founder is 24, down from 30 in 2022, and the number of accepted applicants between 18 and 22 increased 110% last year.

Three forces are driving the uptick in young entrepreneurs.

AI gives younger, inexperienced workers foundational competence across a range of skills needed to launch a business (coding, writing, marketing, etc.), making ideas easier to test, and startups easier to launch.

A cooling job market has made traditional jobs harder to get.

Gen Z grew up seeing the founder lifestyle glorified in the media, markets, even politics. The AI boom has only brightened the spotlight.”

via Prof G Markets

🌀 Re-Framings

A few short re-framings for building better systems or worlds that I’ve recently come across:

🍃 Hard Fascination → Soft Fascination

“Importantly, the benefits of nature do not appear to depend on how much we actually enjoy being outdoors. Some people would find a bracing winter forest walk fun; to others it would be a dreary trudge.

But as long as you aren’t freezing or feeling unsafe in some way, the repair to your fatigued attention through what Berman calls the “soft fascination” of nature, as compared to the “hard fascination” of ostensibly relaxing but mentally taxing tasks such as watching TV, will happily occur anyway. Nature tickles our attention gently — it doesn’t overstimulate us like much of modernity does. […]

“Our relationship with nature is failing,” said Miles Richardson, a professor of human factors and nature connectedness at the University of Derby who led the research. “We are now in an attention economy; there’s a battle for attention and nature is the element that doesn’t have an advertising budget,” he added. “We’ve been schooled out of the wonder of nature; we’ve been primed to scroll through our phones and look for wonder there instead.”

In a world seemingly short on empathy, nature offers a crucial and largely non-political pathway toward restitching our fraying societal fabric. After all, what other single, low-cost intervention has been shown to improve individual health while also chipping away at some of the most balefully stubborn ailments of society, such as loneliness and violent crime?”

» Society Needs A Doctor’s Prescription For Nature by Oliver Milman

🐝 Anthropocene → Symbiocene

“If the Anthropocene began when the Industrial Revolution set industry against the living world, the Symbiocene imagines what should follow: interspecies democracy, life within Earth’s limits, and ecological reciprocity. This is not a future where we engineer nature to fit human comfort and convenience. Instead, creation becomes a conversation: a turning away from our long habit of using technology against nature, toward listening, humility and the flourishing of life.

But how do we loosen modernity’s grip when we’re still dependent on its tools? The answer is solarpunk, the edgy but sincere cultural movement joining technology with nature – reimagining technologies based on conceptions of science that coax rather than torture. The ‘punk’ in solarpunk comes from its blended roots: not rejecting technology like a luddite, nor blindly embracing it like an ecomodernist, but instead yoking technological development to ecological and biological principles to serve the good of the whole. The ‘solar’ element connects the photosynthetic wonder of plants as light-eaters, with the free energy of the Sun harnessed by solar panels and other forces of nature in wind, water and geothermal energy.

Solarpunk’s point isn’t that a ‘solar future’ begins and ends with the devices we already know. It widens the meaning of technology to include Indigenous and place-based practices such as chinampas – raised garden beds woven from reeds, anchored in shallow lakes, and refreshed with nutrient-rich silt from canals. […]

In other words, it treats science and technology as plural: shaped by culture, landscape and values, not dictated by a single industrial blueprint. That’s why solarpunk often turns to biomimicry – learning from nature’s designs – to aim human ingenuity at repair: restoring ecosystems while also restoring the ways we live with one another. […]

The point is not ecology or technology, but the refusal of that split.”

» Compost modernity! by Yogi Hale Hendlin

🫀 Machine Governance → Living Institutions

“Modern public institutions largely inherited a mechanistic model of organization. This model prizes linear planning, top-down hierarchy, standardization, and the relentless optimization of processes for efficiency and control. For much of the twentieth century, such an approach was considered synonymous with good governance. Bureaucracies were deliberately built as rational machines, with clear rules, unitary chains of command, and as little deviation as possible. Predictability was treated as the highest virtue, deviation as failure. This mindset arguably delivered stability in eras when social change was slower or confined. Yet it is proving painfully mismatched to the current era of complexity and upheaval. A governance model that assumes society is a machine, with inputs that can be precisely calibrated to yield desired outputs, falters when confronted with dynamic, non-linear problems. […]

Re-imagining institutions as living systems begins with a shift in metaphor that carries practical consequences. In contrast to a machine, a living system (like an ecosystem or organism) maintains its coherence by adapting to its environment. It is dynamic, not static, defined by processes of growth, learning, and self-correction. Such a system does not achieve stability by freezing change; it achieves resilience by evolving in tandem with change. Consider a coral reef: it hosts a great diversity of species whose interactions create a stable overall habitat, yet the reef is constantly adapting to water conditions, food supply, and external stressors. No central authority governs the reef, yet it manages to balance and re-balance itself through myriad feedback loops. This ecological perspective is a fruitful model for governance. If institutions were conceived more like reefs or forests, as organic assemblages of people, norms, and processes that must continually respond to feedback, they would approach policy and management very differently. They would prize flexibility, observation, and learning as core virtues, rather than treating change as an anomaly to be resisted. […]

Crucially, imagining institutions as living systems is not about romanticizing nature or communities. It is about aligning governance with reality. Human societies are complex adaptive systems. Political life unfolds in ecosystems of relationships, not assembly lines. By acknowledging this, institutions can move away from the futile pursuit of perfect control and toward what might be called collective resilience.”

» Imagining Institutions as Living Systems by Naeema Zarif

🧬 Frameworks

One small, handy framework to build more regenerative, beautiful, and just systems:

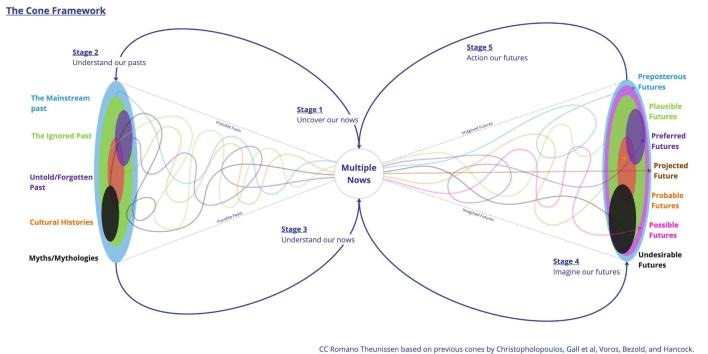

The Futures Cone Reimagined by Romano Theunissen

“In this model, the Futures Cone is not the entry point, it is the midpoint. It sits between sensemaking and strategy, between imagination and decision. Visually, the Cone can be reimagined not as static, but as a dynamic interface. Around it, the five facilitation stages form a series of inputs, shaping and enriching the futures placed within it (see figure 7). The present at the base of the Cone is not a given, but an outcome, co-constructed through reflection, dialogue, and plurality. When used this way, the Cone regains its original power to hold complexity, not simplify it.”

🎨 Works

Some hand-picked, particularly thought-provoking and inspiring work:

That’s it for this week’s Rabbit Holes issue!

Did you enjoy this week’s issue? If so, tap the ❤️. It helps more people discover this and shows me what’s resonating.

Thanks for supporting my work! 😊

Thomas