Rabbit Holes 🕳️ #59

From vegetable money to the interstitium, attention activism, an ecological civilization and superyacht owners

Hi there,

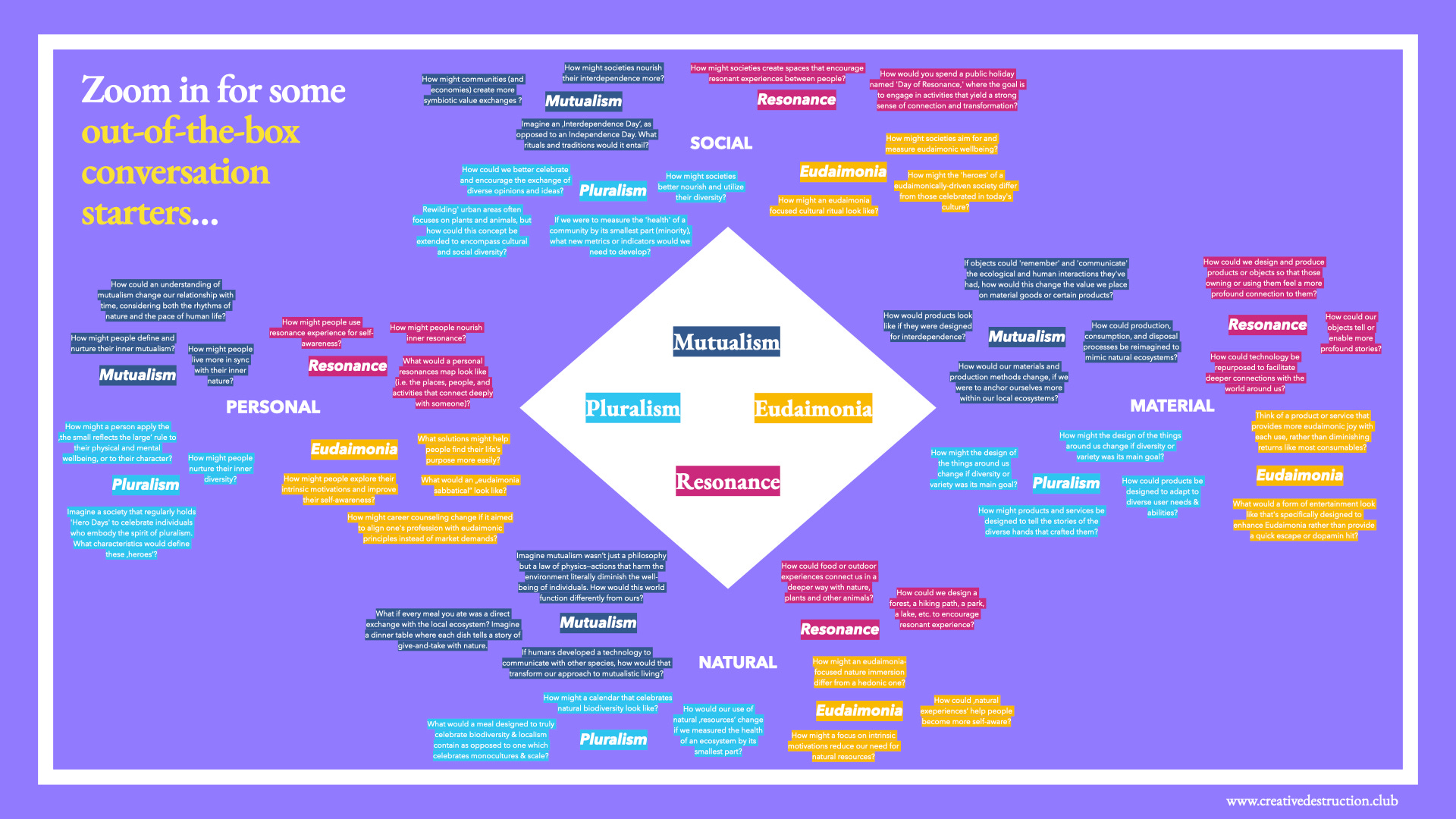

Below is an excerpt from my recently published report Alternative Prosperity: Reframing The “Good Life”. I am currently working on an improved version of the framework that I shared in the report. In case you haven’t checked out the report yet, you can download it here.